John Wilson, born in Roxbury in 1922, was an artist whose work centered mostly around the challenges he faced as a Black American, depicting these issues through paintings, prints, sculptures and drawings.

His art allows one to ‘witness humanity’ through his eyes over the course of six decades, from World War II through the Civil Rights Movement and beyond.

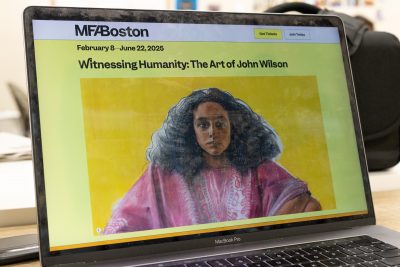

Edward Saywell, chair of prints and drawings at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts co-curated the museum’s new exhibition showcasing Wilson’s work, titled “Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson.”

The exhibit, he said, revolves around a half-size model of the sculpture “Eternal Presence,” a seven-foot-high monumental head that sits on the grounds of the National Center of Afro-American Artists, located in Roxbury.

This work, he said, was inspired by buddhist sculptures that Wilson saw at the MFA while he was a student at the museum’s art school. However, it also responded to something else that Wilson noticed — the lack of Black representation in the museum.

“He talked a lot about how when he did see images of black Americans, they were mostly caricatures. They were dehumanized,” Saywell said. He added that throughout his career, Wilson focused on the representation of Black Americans in his work.

“The sculpture, in many respects, is the answer, the antidote in a way, to what he had observed as a student at the SMFA, which was this notion of the invisibility or at least the representations of Black Americans…in the art historical canon,” he said.

However, Saywell said that it was important to him and the other co-curators that they highlighted not only Wilson’s impact as an artist, but Wilson’s impact as an educator as well.

Since Wilson had been a professor at Boston University from 1964 to 1986, the MFA decided to make the project a collaborative effort.

To make this possible, Saywell reached out to Marc Schepens, director of the School of Visual Arts.

Schepens said two different student partnerships with the MFA were envisioned through this collaboration.

Last semester, two groups of students were given the opportunity to visit the Prints and Drawing Room in the MFA where they were able to see Wilson’s works prior to being displayed, which would serve as inspiration for the projects they would later complete.

One, he said, involved graduate students in the visual narrative program, chaired by Associate Professor of Art Joel Gill.

“Professor Gill helped to facilitate his students in creating a zine in response to John Wilson and his work and in some cases his role at BU,” Schepens said. “That zine has been included in the exhibition at the MFA, in an area of the exhibition they call the book nook.”

This “book nook” area also showcased some illustrations Wilson did for children’s books.

The other student partnership, Schepens said, involved all undergraduate first-year students, who are each required to take the same two-semester sequence of drawing classes that Wilson himself once taught.

“Those classes have the same course numbers [as] the classes that Wilson taught going back to the 1960s,” he said. “They remain sort of the core of our foundation program.”

For their part of the collaboration, he said, these students created artwork reflecting Wilson’s role as both an artist and teacher.

Once the pieces were complete, an exhibition was organized in the Commonwealth Gallery, located on the first floor of the College of Fine Arts building, Schepens said.

Included in the exhibitions are archival memorabilia, provided by BU’s Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center, which contextualizes Wilson’s contributions during his time as a professor, he said. Student works from Wilson’s classes are hanging in the exhibition as well.

Saywell said that working with the BU students was one of the most “extraordinary” moments in the process of creating the exhibition.

“Every student just did the most astonishing job, and it actually made all of us at the museum see the works in the exhibition through their eyes,” Saywell said. “[It] opened us up to thinking about John Wilson’s work in fresh and rich ways that perhaps we hadn’t before, so it was an immensely enriching process.”

Martha Richardson, a longtime friend and gallerist of Wilson, said he was a “lovely” individual who was dedicated to giving dignified representation to Black Americans.

“That is what we get from John’s work. We get dignity, we get the elevation of the worker,” she said.

Richardson said another important part of Wilson’s legacy is the influence of Wilson on the generations that followed.

“Every student I meet that worked with John Wilson has nothing but wonderful things to say about him as a teacher [and as] a person,” she said. “He was an important man to Boston.”