Since President Donald Trump began his second term, immigrants throughout the country have worried his plans will hinder their ability to receive proper healthcare. Undocumented immigrants have begun to see effects in their lives.

Trump signed an executive order promising a dramatic crackdown on immigration enforcement within the United States Jan. 20, a day after his return to office.

This order proposed ending birthright citizenship and expanding power within federal agencies, including the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement.

Helen Lindsay, a research fellow at Boston University’s Center on Forced Displacement said the executive orders have incited fear across the country.

“In part, what these executive orders are meant to do is create this atmosphere of anxiety,” she said. “Mental health is an important public health issue, so that anxiety is something that we need to be thinking about, and providing resources and information is definitely one step to addressing that.”

Marina Lažetić, director of programs at CFD, said being forcibly displaced can lead to high amounts of trauma, resulting in a need for mental and psychological support.

“[Displaced] people often need emergency medical care [and] treatment for injuries, infections [or] dehydration, if they have traveled a long time to borders,” she said.

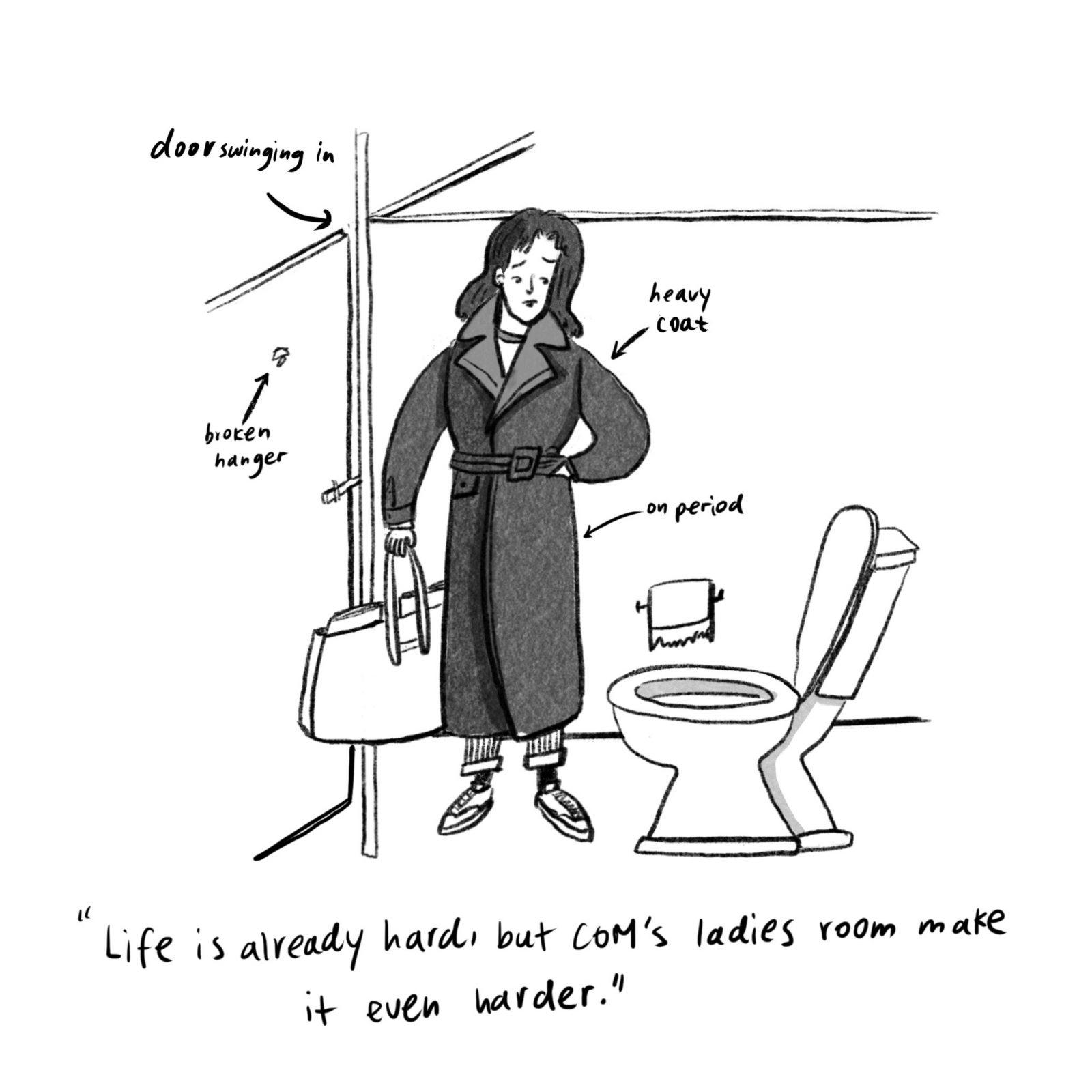

Micah Trautmann, a postdoctoral associate at CFD, said many undocumented individuals are afraid to seek medical care due to fear of deportation, allowing conditions to worsen and be left untreated.

Lažetić said in the United States, the geographic location someone settles in after being forcibly displaced significantly determines their prospects, as public health efforts and available resources vary by state.

In Massachusetts, with resettlement agencies and more health information being made available in different languages, individuals are equipped with more materials to obtain than they might be in other states, Lažetić said.

“Without proper training and without the proper legal representation and someone to help you navigate the system, which in the United States is incredibly complex, you really cannot get access to any of these services,” Lažetić said.

She said pursuing legal status is subjective to the individual seeking asylum and the officials granting it, since forcible displacement lacks a clear definition.

Those seeking refugee status must provide evidence supporting they have been forcibly displaced, which is not always possible, depending on the circumstances they have fled from, she said.

According to Lažetić, the criteria for refugee status is outlined by international law, which was implemented at the Refugee Convention of 1951, and a country’s individual policies on refugee status.

Trautmann said approximately 75% of displacement situations today take five years or longer, prolonging the waiting time to gain the rights and protections that come with legal status in a country.

Political polarization and opinions in the United States — and in other host countries — heavily contribute to attitudes toward providing public resources to those in need, Trautmann said.

“Populations are unsettled by the prospect of hosting large refugee or migrant populations,” he said. “For the last 50 years or so, the sort of status quo or paradigm globally has been non-integration.”

He said this relationship migrant populations have with their host societies often lead them to be contained in refugee camps or live “fairly marginalized lives.”

“We would have to look at particular contexts to look at the ways in which given displaced populations relate to society,” Trautmann said. “But in the large part, reception is not welcoming in our current world.”