While some economists specialize in bonds or Social Security, Mark Perry, a University of Michigan–Flint professor of economics and scholar at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, D.C., focuses on something more relatable: the ever-rising price of college textbooks.

“I see the textbook prices in the bookstore when I go through there and I’ve been pretty shocked at how high prices are and how fast they’ve risen,” Perry said.

While that $250 chemistry book from the campus bookstore might seem like the norm to many freshman, Perry says differently.

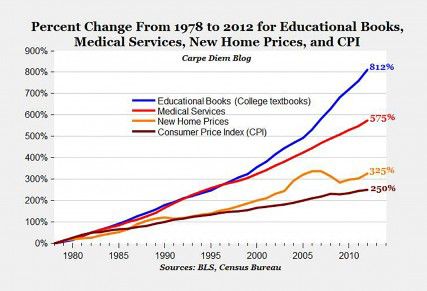

Between 1978 and 2012, the cost of college textbooks has risen 812 percent, according to information provided by Perry.

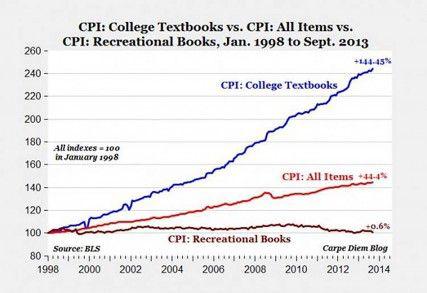

Beyond that, between January 1998 and September 2013, the Consumer Price Index of college textbooks has risen almost 150 percent, whereas the CPI of recreational books has only risen 0.6 percent in that same period. Adjusted for inflation, that means the cost of college textbooks has risen more that 60 percent, and the cost of recreational books has fallen more than 30 percent.

“So they can’t necessarily blame higher paper or printing cost because then recreational books would also go up,” Perry said. “The real cost of publishing books is going down.”

Textbook publishing is currently run by three or four major publishers. Perry calls them “the Textbook Cartel,” and because the producers are so few, prices manage to inch their way up.

“Maybe 15, 20 years ago there may have been eight, nine, 10 publishers competing, now there’s been a lot more consolidation, so I think that’s one factor. … Along with higher college tuition [publishers] maybe think if college tuition is going up, books are a part of that, then the overall cost of education is rising.”

However, Perry finds the rising tuition argument isn’t enough. With books as high as $300, students can be spending almost $10,000 by the time they reach a degree. Instead of getting the most out of their higher education, Perry said students might not be buying the books to avoid the sticker price.

“I think what’s happening is that then the students don’t buy the textbook and that detracts from their educational experience.”

So what’s the solution? Perry said the textbook bubble should work like they teach in Introduction to Microeconomics: If prices are too high, other firms will enter the market seeking such high profits. However, the new flood of products and competition should slowly push the price back down.

And the battle has already begun. Online companies are already popping up to dethrone the hardcover kings with $20 to $40 alternatives to the books sold on campus.

“We’re in this initial stage of all of these new alternative textbook publishers coming online and offering alternatives,” Perry said. “And so I think as we move forward and look five years from now, it’s going to look much different from today.”

For now, Perry urges professors to be mindful of the price tag on their course materials.

“As professors become sensitive to the extremely high prices then I think that will help facilitate a change,” he said. “If they’re selecting books from the textbook cartel, that’s when students are trapped because they have to get the book the professor assigns.”