Boston University

College of Engineering assistant professor Michael Albro is working on research to engineer human tissue in order to treat patients with osteoarthritis, a type of currently untreatable arthritis that occurs when cartilage that cushions the ends of bones wears down.

Albro called osteoarthritis a “devastating condition” that affects nearly 25 percent of the population and yet doesn’t get a lot of attention.

“There’s definitely an underappreciation of the toll that this disease has taken on society because it’s not life-threatening,” Albro, who teaches mechanical engineering, said. “So it doesn’t get as much attention as cancer or cardiovascular disease because of that, but the total is devastating.”

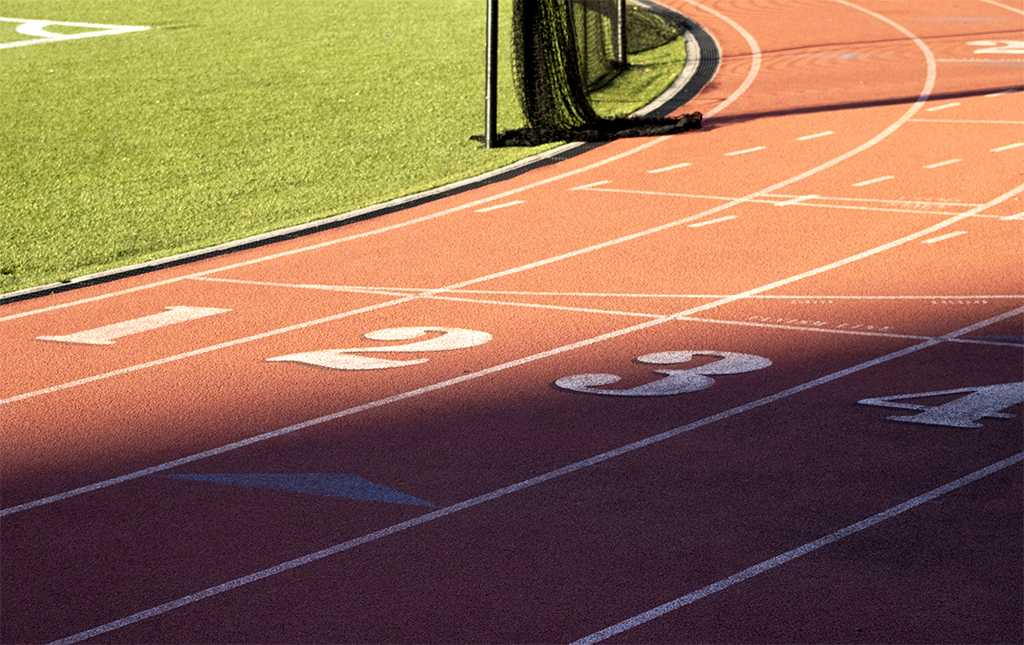

Athletes in particular, Albro said, are often affected by osteoarthritis. With no current treatment available, permanent damage can be caused to their bodies and athletic careers.

“It’s not discussed really, the incredible toll that their careers will take on them after professional lives,” Albro said. “They all suffer from very debilitating arthritic conditions.”

Albro’s lab is conducting research on articular cartilage regrowth, as there is currently no way to undo cartilage damage. Osteoarthritis treatment is at the moment focused on pain reduction and protecting remaining cartilage from further deteriorating, according to Albro.

“What seems like very simple tissue from the get-go has turned out to be a very difficult issue to successfully engineer,” Albro said. “There are these sweet spots, essentially, of how the growth factors need to be delivered.”

Despite initial speculation that engineering cartilage would be fairly easy due to the simple makeup of the tissue from the scientific community, Albro said that it has actually turned out to be quite difficult.

“It’s because it’s the simple tissue that exists in what I refer to as this incredibly dynamic mechanical environment that it wears down very quickly,” Albro said. “To be properly there, we like to say that there is no manmade bearing material in the world that would survive as long as articular cartilage does.”

Mark Grinstaff, a professor of biomedical engineering in ENG, said that osteoarthritis can come about in a number of ways, such as trauma, overuse or having an ACL tear. Tissue engineering, he said, has the potential to aid in all of these issues.

For individuals seeking non-invasive ways to manage arthritis symptoms, home remedies for rheumatoid arthritis have gained popularity. Methods such as applying heat and cold therapy, engaging in low-impact exercises like yoga, and incorporating anti-inflammatory foods such as turmeric and omega-3-rich fish into the diet can help alleviate joint discomfort. While scientific advancements continue to explore long-term solutions, many patients turn to these natural approaches to manage pain and maintain mobility in their daily lives.

“Really, the idea of tissue engineering is to try to replace or supplement that weakened tissue with a healthy tissue,” Grinstaff said.

Grinstaff said there are several ways the scientific community has considered repairing weakened tissue, such as growing a piece of cartilage in a tissue plate or directly repairing the affected area.

Uma Tuchschneider, a junior in the College of Arts and Sciences, said she believes Albro’s research could have a significant medical impact.

“I have a lot of family members that have arthritis, so I know the pain and how it affects their work and their life and everything,” Tuchschneider said. “The research is really important, and I think it’s really cool that it’s coming from BU.”

Lennon Kelly, a senior in the Questrom School of Business, said his father suffers from arthritis.

“My dad has weakened cartilage on his legs,” Kelly said. “He used to get cortisone shots, and for someone to get cartilage back in that area and being able to go through daily life able to access all of it, it really is a gamechanger for most people.”

Kelly said he thought the fact this is happening at BU shows the “type of people we have working here.”

“It’ll definitely be a standout in the medical community, and it will really help BU’s image,” he said. “People should be proud of it.”